Nomad

Joe Casey

joe_casey_writer-mail@yahoo.com

Author’s note: Nomad and The Sandalwood Box are, in a sense, two ends of the same story. The Sandalwood Box was written first, followed some time later by Nomad. One does not need to read them in any particular order, however.

I want to say that I believe I was the first of us to notice him. That may or may not be true, of course; I have no way of knowing, but I still believe it to be true. Why I noticed, of course, I had no real idea, not back then; he was there one day, in the corner of my eye, sitting by the fountain on the plaza, some exotic bit of something in a wrinkled white linen shirt, well-worn denims, sandals fashioned from the skin of some Nilotic animal, a largish backpack resting on the ground by his feet.

I looked, looked again, saw him looking back, turned away, kept walking.

Turned back once again, and he was gone. I smiled at my absurd self, blissfully ignorant.

—

Of course, I know now why I looked. That, perhaps above all, was what he left with me, that semester. The others may have their own stories to tell. Especially Barbara. If we knew where to find her.

—

That image of him stayed with me, that evening, as I sat across from Martin in our apartment. I could still see him in my mind; more details came to the surface, or were perhaps invented by me. The way his shirt, nearly translucent, had been unbuttoned halfway down his smooth, flat belly, exposing the coppery coin of a nipple. The way the afternoon sun had glinted off his long, curling black hair, so like a goat’s. The way he’d leaned back, legs crossed, arms arrayed behind him, supporting himself, as he’d turned his head up to the sun, smiling beatifically.

But how to speak of it? I noticed a man this afternoon on campus, seemed wrong. I was not normally in the habit of noticing men, let alone remarking upon them; that was something I left to Martin, who noticed them with some regularity.

I rephrased it in my mind. So, there was this guy, today, on campus…

Same thing, but different.

I said nothing to Martin, took up my wine instead, took a sip, took a bite of the pasta.

—

We thought we were brilliant, of course, the five of us, smug in our delusions, thinking we had everything figured out, thinking that our time here had done nothing but perfect perfection. We would be loosed upon the world, sooner perhaps than was good for us (or the world), to dazzle and confound it with our genius.

We lorded over it, we held court, we opined, we deigned to speak to others, we propounded.

How clever we thought ourselves! How brilliant! How unique!

We knew nothing, of course.

—

He was there, one day, some Tuesday… already there when I sat down. He sat next to Barbara; had she been his ticket, his way in, his key? Had she, too, seen him that day or some day, sitting on the plaza? Had she doubled back where I had not, to confront him and his audacity?

I glanced at him, glanced again, eliciting some small smile of recognition from him, though he said nothing, gave nothing away. I nodded a brief greeting to him, turned to listen to Paula.

Up close, he was older than I’d thought… late thirties to my early twenties, that alone perhaps reason enough to reject him. Not a student, obviously. Faculty? He never said; subsequent investigations by me and Robert could neither confirm nor deny this. The university’s bookkeeping went only so far, we thought. Somebody had to fall through the cracks sometimes.

There was some doubt, even now, as to his provenance… if that was a word that might be used to describe his origins. Barbara, inexplicably, thought him Indian or Pakistani, although she—a Briton confronting the tattered remains of empire—tended to lump every non-Caucasian into the same group. Robert, I think, was nearer to the mark, pegging him for someone North African, although that alone ran a gamut of many thousands of miles, encompassing everything and everyone from Rabat to Eilat, Algiers to Khartoum. Paula, when pressed, gave him residence in some teeming slum huddled halfway up some mountainside looming over Rio or São Paulo.

I held my judgment in reserve; it didn’t matter one way or the other, although I sided more with Robert.

Up close, one could see the history behind him, etched in the fine wrinkles parenthesizing his eyes, his mouth. He was of a color I’d always associated with exotic spices, exotic woods, but it was more than that. It was the color of coffee mixed with milk, some rich yellow/red/brown hue… almost tobacco, almost ochre, almost umber. His teeth were whitest pearls set within the sensuous bow of his mouth. His eyes were a smoky topaz under hooded lids.

He was—even in our polyglot multicultural community here in Berkeley—an outlier.

And when he spoke, finally, responding to one or another of Paula’s many small idiocies—she, alone, of all of us perhaps failed ever to appreciate fully why she was here, what she could have achieved here—his voice was… well, the term mellifluous came first to mind, although I cringe even now to write it, but there it is. A well-modulated tenor, such as one might hear from some of the better-trained evangelists, a voice designed to convince, to coerce, to coax, to urge.

And we listened. How we listened!

Enough stories there for a lifetime or two or three, improbabilities, for the most part, seemingly spun out of whole cloth; if only one in ten were true… well, then, there’s Scheherazade put to shame.

And, yet, we listened. How we listened!

How could we, we thought, have gotten through six years of school without knowing any of what he told us? How incomplete our knowledge! Had our teachers lied to us? What complicities lay behind our education; what vast conspiracies?

We wondered why he had chosen us and not some other group; people like us were legion.

—

When I was a child, I received as a birthday present one year—my thirteenth?—a book, a paperback with a red cover, wherein were tabled a thousand or so words, each glossed into twenty-six languages. I pored over the book for hours, delighting in the likenesses and differences among languages, attempting to pronounce each word in the absence of any guide, surely slaughtering them all.

That was like listening to Michel.

It was the only name he ever gave us, as if that were enough. One name sufficed for Jesus, he would tell us, laughing, and we accepted it. Lenin, Stalin, Mussolini, Hitler… we countered, to his amusement. Gandhi, he tossed back at us. Buddha. We parried with Mao.

He and I joked, on occasion, about our own names, about the similarity. Michael… Michel. Alike, but different. Two sides of the same coin. And thus he had me.

When one language failed him, another would do. Each of us had, in his or her command, one or more of these languages: Robert, his stalwart German… I, my beloved French… Barbara, a surprising command of Italian. Even Paula possessed a tourist’s working knowledge of Spanish.

The rest, we trusted to him. Arabic, Turkish, Portuguese… even a sibilant and spluttering Russian. None of us could decipher it completely, relying solely on context for understanding. One might imagine that one were conversing with a particularly gifted idiot savant.

Except for his beauty.

That, too, we fell prey to. All of us. Even me.

—

Where did he stay? we wondered. Easy, enough, on this campus to find a crack or a crevice to slip into when others weren’t looking; I wondered, sometimes, that we hadn’t been overrun with a horde of such individuals, living on the cast-off largesse of this institution and its benign ignorance.

He was there every day, when we met in the Union; he outlasted us as we scattered in the gathering dusk to our various commitments.

—

And then, one day, some Tuesday, I came home to him, in our apartment, what meager possessions he had had squirreled away in that backpack now neatly unpacked into our already-crowded and cramped bachelorhood.

I fixed Martin with a grim stare; he, fittingly, failed to meet my gaze.

“Is he going to pay his way, at least?” I offered, to bated-breath silence.

“I… don’t know.”

“Martin…”

He managed some embarrassment. “I know.”

“Be careful.”

He shrugged, smiling ruefully. “How?” And I understood.

—

Into Martin’s bedroom, soon enough, with all that that entailed.

Any arrangement of three or more individuals sharing the same space invariably becomes a contest of wills, and so it was with us. I could hear them, most every night, at work in the bedroom, the soft sounds of passion, stifled but not enough, wafting out into the still night air.

The mechanics of it I knew well enough, or could intuit… and could not stop my brain from doing so; only so many orifices, only so many means to penetrate them. I had known from an early age what Martin was and what he wanted, marveled at this most intrinsic difference between us where no other difference existed. But for minor things—a misplaced mole, a blemish here and not there—we were the same person.

Except for this.

I had Paula, if I wanted her, and she me. A tacit arrangement existed between us, mutually agreed upon not so much by words as by some unspoken contract comprised of ellipses and silent acquiescence. We saw each other as necessary, allowed our bodies to meet as necessary. Whatever might happen between us would certainly do so only because we failed to step out of its way.

Ever the Midwesterner, Paula was practical and prudent and pragmatic and principled, sure of her opinions to the point of intransigence… someone to whom another someone of a less directed nature, shall we say, might anchor himself. I have no doubt that she could see the twinned rails of her future shining before her, each mile measured and marked with assurance. My future—even at this late stage in my academic career—was more… aleatory, I realized. Perhaps Paula was what I needed.

—

With Michel, Martin became less guarded, more open, more voluble, surprising those of us who thought we knew him (as well as this person, who grew up with him) with a clever—but never cruel—wit and candor, a deep and questioning intelligence, an ability to shape and mould language, and I knew then that this was what he would do with his life.

It was interesting to watch my brother with Michel, to watch them conduct this thing in the open—as much as they dared—and to see also the slight discomfort that Martin felt while doing so, knowing that I was watching.

“It bothers you,” Martin said to me, one evening, when he and I were alone.

“It doesn’t,” I answered.

His mouth quirked. “I see you, watching us all the time.”

“Given that you’ve moved him in here, I don’t have much choice.” I hesitated, then went on. “I think it bothers you.”

He frowned. “Why do you say that?”

“Because there’s so much more that you want to do, and feel that you can’t. Not around me. Not around us.”

“Like you and Paula are with each other,” he gave back to me, his voice flat.

“Well…” I equivocated. In truth, Paula and I were even more circumspect in our public lives than Martin and Michel, something that Martin, it seemed, had noticed.

“Is she what you want, Michael?”

“We’re talking about you and Michel.”

“Oh. Of course.”

—

This conversation—regardless of Martin’s true intentions in starting it—had one effect on me. It led me to seek Paula out more and more often, to… well, to take the bull by the horns, or however you wish to say it. At least to see what was there between us and whether it was worth fostering.

She would leave for Chicago as soon as she could; I knew that. She had never truly been happy out here in our lesser paradise with the rest of us, had never warmed to the place or the culture. I knew that any future I might have with her would involve moving there with her; I would never convince her to stay here.

Could I leave this place, where I’d grown up? Martin, I suspected, would not; what would my life be without his constant presence?

“Are you ever afraid?” I asked her, one evening, over dinner.

She sat back in her chair, one hand playing with the stem of a wine glass. “What an odd question. Afraid of what?”

I shrugged. “I don’t know. Everything. The future. What you’ll do with it.”

She chuckled. “Oh. I thought you were going to bring up something really serious.”

I smiled. “‘Make no little plans…’”

She smiled in return, furrowed her brow in thought for a long moment. “I don’t know,” she admitted, finally. “Maybe. Sometimes.”

“You never show it.”

She smiled. “I’ll try to look more abjectly panic-stricken in the future.”

I chuckled. “I meant it… well, as a compliment, perhaps. Me, I’m scared shitless half the time.”

She frowned again, thinking. “I don’t know. I guess maybe it’s that I know what I want, know that I have the means and the tools to get it.”

“Well, that’s good. That’s a good thing.”

“I hope so. When I say it out loud, it sounds like I’m a scheming bitch.”

“Well, that’s why I find you so attractive.”

She smiled and rolled her eyes. “Thanks.” I reached out for her hand as she continued. “I suppose—if I look at the future as one big thing, sixty or seventy or eighty years of it all at once—then, sure, I get scared. I think we all do. But… I don’t think of it that way. I break it up into pieces. First this, then this, then this… all the way to… well, the end, I guess. In the end it all ties together, of course, but it doesn’t necessarily start out that way. I know what I want for… oh, I don’t know… the next five or ten years and then, after that, who knows? Something else.”

There was something about her, that evening in the restaurant, that struck me as lovely. Some softness—perhaps afforded by the dim light from a candle—shadowed her face, blunting its normally harsh contours. Paula had never been—even by her own admission—a “pretty” girl; there was actually something quite mannish about her, about her physicality, that found its way into her psyche, as well. I think part of me responded to that rather brusque directness about her, as if I could share it with her and become a more… motivated and determined person because of it.

And, God help me, as I sat there, holding her hand, I almost asked her.

I almost did.

—

Shortly after Michel regaled us with a tale less improbable than many he told that semester, we lost Robert.

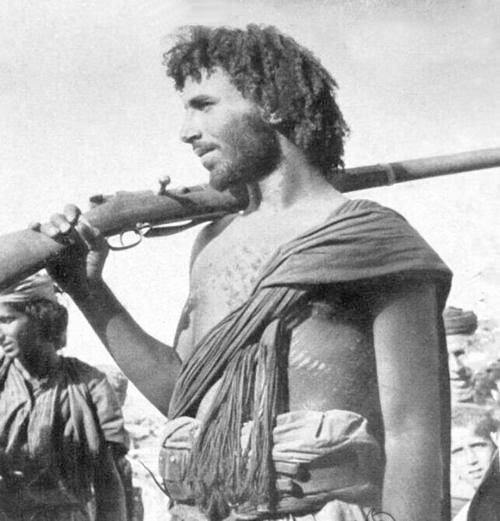

I can’t even remember now what the story was about… something involving freedom fighters and an insurgency in some typically and perennially war-torn Middle Eastern country, a much-younger Michel one among them in a turban, toting some appropriately Russian or American sub-machine gun, depending on the nature of the adversary.

One particularly salacious detail in this story was that, at some point, one of the fighters—a tall, grim, gaunt man in his late thirties—had taken Michel as a lover.

We all listened to this tale with varying degrees of suspended disbelief; the tale itself was exciting enough—worthy of a top-notch writer of thrillers—but when presented under the guise of truth, well…

At the story’s conclusion, Robert started hammering Michel on the details. Michel held his own for far longer than we would have thought, until he finally fetched up—or claimed to—against the limitations of his abilities in English and we stopped being able to follow the story.

Robert stood up, pursed his lips, gathered his book bag, opened his mouth to say something, closed it again, and strode off, not looking back.

The rest of us stared at each other until Barbara murmured something designed to console Michel—and perhaps my hapless brother, uncomfortable with the erotic aspects of Michel’s tale—before going after Robert.

—

I met Robert alone, a few days later, at his request, at a café well away from campus.

“I don’t like bullshit. I never have,” he said, by way of explanation.

“Well, it’s all bullshit. What did you expect?”

“The question is: why are we listening to it? Why do we indulge him?”

I shrugged my shoulders. “Because it’s fun? It’s entertaining?”

Robert rolled his eyes, exasperated. “If that’s the kind of entertainment you like, have it it. Not to my taste. Sounds… I don’t know… wrong. Decadent.”

“C’mon, Robert…”

“I don’t like him.” Robert surprised me with a truculent look on his usually placid face.

I chuckled. “That much is obvious.”

“He’s dangerous.”

I frowned. “He’s harmless.”

“Do you think so? Look at Barbara. She’s ready to start a cult, with him as its leader. That’s not ‘harmless’, not in any way. The last person I would have pegged to get involved with anything like that is Barbara. I mean—good God! Barbara! She wouldn’t bat an eye if Christ himself showed up one day on campus. And now look at her. That’s how things like the Manson Gang or Jonestown get started.”

“I think you’re overreacting.”

Robert said nothing, stared at me for a long moment. Then, “How do you feel about him and Martin?”

I didn’t respond, not immediately. Robert stared at me, his truculence changing into an expectant smugness, knowing as well as I did that I didn’t like the idea of Michel and my brother.

“I warned him,” I admitted.

“See? Even you feel this way, even if you won’t come out and say it. You need to stop it, Michael. Him. You need to stop him.”

“What, exactly, do you think he’s going to do, Robert? What, exactly, can he do?”

Robert shrugged. “I don’t know, Michael. I just don’t know.” He paused, and a frown creased his brow. “And you might want to talk to Barbara about… things.”

—

I sat there, mouth open, eyes wide; the person across from me would have been culturally entitled to use the word ‘gobsmacked’ with no irony or pretense whatsoever. Instead, she looked at me coolly, those crystalline sapphire eyes hooded and distant.

“You’re kidding,” I finally managed. “How long? When?”

“You remember the day he showed up.” Not a question, and answer to my questions.

“But,” I started. “Martin…”

She managed to look somewhat sheepish. “I know. That part of it is… difficult. Sharing him. It bothered me at first, but then I started thinking about it. Given what he is, how could it be anything else? And I can live with that. For now.”

I wanted to slap her, refrained. Instead, I asked, “Does Martin know?”

“I don’t know, Michael. You live with him; do you think he knows?”

“No,” I muttered, after some thought. “I don’t think so. I think I’d know.”

“Are you going to tell him?”

I knew the answer to that one. “Absolutely not. If anyone is going to tell him, it’s going to be you. Or Michel.”

“Well, then…” She gestured, helplessly. We stared at each other, at some kind of impasse. Barbara shifted under my gaze. Then, “I assume you’re here talking to me because you’ve been talking to Robert.”

“Yes.”

“How is he?”

I shrugged. “I don’t know. He’s… Robert.”

She smiled. “Yes.”

“He thinks you’ve lost it.”

“He does? Why?”

“He thinks Michel is dangerous, that he’s going to do something, or make someone do something. I don’t know; he wouldn’t explain it. Or couldn’t. He mentioned Jonestown. Manson.”

She barked out a surprised laugh; heads turned, but she ignored them. “Seriously.”

I shrugged again. “That’s what he said.”

“And you?”

“I just don’t want to see Martin hurt.”

“Martin’s not a child.”

“I know that, Barbara.” I struggled to keep the anger out of my voice. “He’s just my brother.”

She said nothing, leaned back in her chair, tapped out a quiet rhythm with her fingertips on the arm of her chair, thinking of a response.

“He needed a place to stay,” she said, finally. “I would have taken him in, except… well, Deirdre, of course, and my place is so small; we’d be on top of each other. So… you got him. All the better that it turned out that he found Martin… available, as well. Cements the deal, so to speak. So, at least Martin gets to wake up next to him and go to sleep with him, while I… well… I have to wait my turn.”

The urge to slap her rose up again; I tamped it down. “I think Robert’s right,” I retorted. “He is dangerous. And you have lost it. You’re not the Barbara I thought I knew.”

She smiled, again. “Robert, Robert, Robert,” she echoed, her voice petulant. Again, the tocsin beat itself out against the armrest. “Ask yourself, though, Michael… why do you think Robert is angry at Michel? Why do you think Robert left? And why do you—all of you—think you know me so well?”

She got up before I could respond, was gone before my brain put it all together.

And that was the last I saw of her, for quite some time.

—

After that, Michel surprised me one day by asking me to join him for breakfast, not at the Commons—our usual hangout—but at some greasy-spoon kind of place off-campus, in town. I’d never been there, had only walked past it periodically on my way somewhere else.

I had assumed that Martin would be there, as well; he wasn’t, to my surprise. Ever since Michel had moved in with us, there was a strange and uncomfortable dynamic among the three of us, with me as the odd man out, in several ways. We each went about our business, remained polite with one another, but it was awkward and clumsy. Perhaps this meeting was designed to ease the tensions between us. Among us. But Martin should have been here, I thought.

I sat down across from Michel. He was dressed today in clothing I had not seen before; presumably, Martin had bought it for him. He looked refreshed and handsome, but then, again, he always did. He pulled out a pack of cigarettes—he favored Gauloises—along with a tiny gold lighter, stuck a cigarette in his mouth, prepared to light it.

“I don’t think you’re allowed to smoke in here,” I said.

“Vraiment?” he muttered, around the cigarette. I nodded my head. Smiling and rolling his eyes at the legal machinations of Californians, he pulled the cigarette out of his mouth, tucked it and the lighter—a Colibri, I thought; expensive, I knew—in his breast pocket.

A server placed coffees in front of both of us and asked about food. We both shook our heads, and she walked away.

We stared at each other; if there was any speaking to be done, I was going to let Michel go first.

“Bonjour,” he started.

Safe enough. “Bonjour,” I replied.

The rest of the conversation was pleasant enough, but not what I expected. There was no apology, no understanding that it was difficult for the three of us to be living together, no promises to do better, to behave better, in the future. No promise to help pay for living expenses.

No mention of Barbara, or Robert.

But for the fact that it was simply he and I facing one another across the table, it was a conversation we could have had in the larger group. I didn’t know what he expected of me; I wondered what he thought as he faced me, a person who resembled his lover in every way except the most obvious one. Perhaps that was what he wanted: to be reminded of Martin without having to respond to him in any kind of personal way. I cast about for a way to extricate myself from this place, and him. All of this made me uncomfortable.

He leaned back, cocked his head, looked at me silently for a long moment. I returned his stare with one of my own. Finally, “I never worry about which one I’m talking to.”

It took me a second to understand him. “Which one—oh, no. We’ve never done that.”

He chuckled. “No. There would be no point, right?”

I smiled. “No. Martin is… well, Martin.”

Another long moment passed between us. Michel reached out for his coffee, drained the last of it in one long swallow. “And what is Michael?” he asked, smiling.

To which I had no real answer, not in this context, not for him.

—

The rest of that morning passed pleasantly enough. I ran errands, spent an hour or so in my favorite bookstore, walked idly through campus on my way home.

Where I found Martin, shouting into the telephone, obviously agitated, nearly in tears. Some wild part of me hoped it was Michel on the other end, that the business with Barbara had finally been found out, but out of the staticky squawking issuing from the speaker I could gather enough to know that it was our mother, instead. He ended the call, turned to me.

“What happened now?” I asked.

He blew out an exasperated breath; his hands were shaking. “More of the same. Some—well, another—huge row between her and Daddy. He’s seeing someone, and she wants to throw him out, but he won’t leave.”

“Well, it is his house, too, after all. And he’s been ‘seeing someone’ for a long time.”

Martin smiled, tensely. “I told her that. I never knew Mom knew that many curse words.”

“Well, it’s all that time that she spent in the Merchant Marines,” I quipped.

He smiled again. “Normally, I’d laugh, but…” He threw himself on the couch, leafed through the paper before tossing it aside. “God, I wish they’d just end it, one way or the other. Either split up or kill each other. I’d be happy either way.”

“Should I go over there?”

He looked up at me, gratefully. “Would you?” I knew that he hated going to our parents’ house; too many fights in the past had been about him, about his coming out, and he hated being reminded of that.

—

Martin’s sentiments about our parents echoed through my exhausted mind as I tiptoed up the staircase to our apartment. After wasting nearly an entire day with our parents, watching them snarl back and forth at each other like feral dogs, I could have happily wielded whatever instrument would be responsible for their demise.

It was well past midnight, nearly one o’clock in the morning. I’d walked back from Paula’s (she’d graciously lent me her car), had refused her offer of a ride back to the apartment, had walked instead. Campus at this hour was beguiling, somehow, mysterious under the silvery wash of moonlight, calming.

But not calming enough. Now that I was home, a last bit of the anger and frustration I’d felt about my parents washed through me, directed now at Michel. He’d obviously not come home after our breakfast, had not been there when I came back to Martin’s conversation with our mother. I knew he’d been to see Barbara, playing one off against the other; I resolved to confront him about it in the morning. I hated his lying to Martin.

I slipped into the apartment, closed the door behind me and turned the deadbolt. I wanted nothing more than to fall into bed, walked instead into the kitchen and rummaged through one of the cupboards, coming out with what turned out to be whiskey.

Good enough, I thought, and reached back in for a glass, poured some of the whiskey over a couple of cubes of ice, prepared to go out onto our balcony and sit for a bit before retiring.

But I wasn’t alone; out of the corner of my eye I saw some movement from the balcony that overlooked the street below. I could see someone standing there, at the balcony… a tallish, thin figure, with curling black hair.

Michel. And when my tired, grit-crusted eyes could focus, something else revealed itself.

He was naked.

I watched, amazed, as he stood there at our balcony, three stories up, unconcerned with his nudity, not caring who might see him. For the first time in my life, I experienced what I imagined a voyeur must have felt, looking through windows, watching while remaining unobserved… some electric thrill comprised of equal parts of eroticism and guilt.

Leave, I told myself. I set the whiskey down on the counter, told myself to move, could not. I could do nothing but watch.

Periodically, a haze of smoke curled up over his head; he must have been smoking. Both Martin and I had been adamant about him not smoking in the apartment; in that, at least, he obeyed us, going outside to do so.

He was bent forward, elbows resting on the rail. I doubted very much that anyone in the surrounding buildings could see very much, if they were awake, but the view from my side was clear. Moonlight washed over his muscular back, slender hips, and the upper curves of his compact and muscular bottom.

Leave, I told myself.

He stood up, then, and flicked the spent cigarette over the edge of the railing, turned.

And saw me.

We stood there, on opposite sides of the glass door separating the living room from the balcony, watching each other silently.

He smiled, slowly, leaned back against the rail, allowing the moonlight to wash across his body, his beautiful body. I had intuited what he must look like, under his clothes, had been given a tiny glimpse of that body the day I’d seen him at the fountain, with his shirt unbuttoned. Now, nothing was denied me.

He had the body of a dancer, trim and lithe and wiry, muscles etched onto his frame. I knew that, thirty years hence, he would look much the same, would be slender and graceful where the rest of us had softened and sagged into our late middle ages.

Something else came under my gaze, drawn inexorably there; could he see my eyes moving there? Could he see the motion of the light in my eyes as they dropped to there, at his midsection?

I exhaled a nervous breath, watching him, watching it, a generous—exorbitant!—gift of flesh, there, flaunting itself, absurd and impressive even in its flaccidness.

Michel grinned wider, slipped a foot into the railing behind him, thrusting out his hips towards me in silent invitation. His manhood bobbled there as his weight shifted, a pendulum of desire, of invitation.

Leave, I told myself. I compromised; I shook my head slightly, turned away, but not before I saw his smile transform itself into a knowing smirk.

Facing away from him, I heard the door slide open and shut behind him as he entered the room. I could sense his passage in my peripheral vision. I could smell the rich musk of his rutting on him as he passed. When I heard the door to Martin’s bedroom shut behind him, only then did I dare breathe.

—

Three of us, now—four, with Michel; was that Michel’s secret? To divide and conquer, to interpose himself as some kind of catalyst into a group, watch it unravel, pick it apart slowly, molecule by molecule, change it into something else?

We still met every day, at the Commons. We were a quieter group, now that Robert and Barbara were gone. I still saw Robert occasionally, apart from the others, let no one else know that I was doing so. I missed him, missed his keen intelligence, missed his humor and skepticism.

I had no idea if Michel still saw Barbara; I couldn’t very well ask him. He still lived with us, still shared Martin’s bed.

“We should do something,” Paula started. No one responded. She looked around at all of us; she—quicker than I—had understood what was going on between Barbara and Robert, had assumed—correctly—a lover’s quarrel, though she had not yet discovered the cause of it.

“C’mon, guys,” she persisted. “We’re just sitting around staring at each other.”

I felt sorry for her. “What about the beach?” I asked.

“Yes! That’s an excellent idea!” She looked around at the rest of us. “Stinson? It’s warm enough; we should go on a weekday… avoid the crowds…”

—

So, Stinson.

Martin and I used to come here as kids, with our parents, driving over for the day from Mill Valley, going up into the woods, up to the top of Mount Tam to look at the city, the beautiful city across the Golden Gate, surely the most beautiful city anywhere, we thought.

Happier times, then. Our parents were different people, then, happier, both with us and with each other. Martin and I were happier, as well; Martin’s differences had yet to start manifesting themselves in moody silences and hours spent alone in his room.

The four of us were in Paula’s BMW; it was a hand-me-down from her father, intended only to get her through school, but it was nice enough, solid under paint gone flat and toothy in the salt-laden air. I sat in front next to Paula, watching her drive, delighting in the precise and machine-like grace of her movements. Martin and Michel were in back.

Conversation was quiet, desultory as we made our way through the city, then across the bridge into Marin. I had the sun visor down, ostensibly to shade my eyes, but its makeup mirror allowed me a glimpse into the back seat. There was an intimacy between the two men that was not out of place here, of course; fascinating to watch.

We passed the exit to our parents’ home; I thought Martin might say something—especially after my last visit—but either he didn’t notice or had done and chose to stay silent. No matter.

There was, among the four of us, a certain change in how we related to each other. Part of that, of course, was because two of us were AWOL, but part of it was the summer itself, rushing to a close. We had managed to eke out the last of our independence and our brotherhood this season; soon, we would have to make hard decisions about our futures. Paula, of course, had already made hers, had perhaps made it the day she stepped onto campus, six years ago, fresh from the prairie.

I, I assumed, would follow Paula. Our tacit agreement and our inertia had bound us even closer together; soon, I imagined, I would ask her to marry me, and I knew she would say yes.

Less certain, of course, was the situation between Martin and Michel. In the shadowed background to all of that was Barbara; I had no reason to think that Michel had stopped seeing her. Neither Martin nor I were in our apartment every waking hour; Michel had every opportunity to go see Barbara in our absence.

That night, when I’d come home late from seeing my parents, had surprised a nude Michel on our balcony, unconcerned, smoking his Gauloises—and where had the money for those come from? I wondered—was still forefront in my mind. It was not the nudity per se that bothered me—I had, in the course of my twenty-four years, experienced my share of casual male nudity—but some kind of uncomfortable overfamiliarity that had manifested itself between Michel and me that night. I had reacted to seeing him naked, had reacted to his prodigious masculinity; he had noticed that I had noticed.

Had he planned on that? I wondered, known that I would come back late and thus conveniently catch him in some post-coital state of reflection. I couldn’t—given his still-secret trysts with Barbara—say that he hadn’t, that he wouldn’t.

Periodically, I noticed him staring back at me in the mirror, from the back seat.

—

Even for a Wednesday, Stinson was more crowded than I would have thought; sun-starved San Franciscans left no opportunity for recreation unused. We managed to find a parking space and walked single-file through the dunes to the beach, where the infinite Pacific stretched away from us towards the other side of the world.

I could tell that even Michel was impressed; certainly he’d seen other beaches, other places like this… but with the mountains rearing up behind us on this tiny spit of land, and with the San Andreas grinding slowly away at itself right under our sandaled feet, Stinson was a special place. Martin and I looked at each other and smiled, each of us remembering.

We set up our towels quickly; we’d all been clever enough to wear our swimsuits under our clothing and began undressing, each facing away from each other, nearly at cardinal points.

When we turned back, I stole a quick glance at Michel, and nearly gawped. My first thought was that he had forgotten to wear a swimsuit and had been relegated to his underwear, but a second glance showed me that it was indeed swimwear.

What there was of it. It only accented what it thought to conceal, barely two patches of cloth bound together with a strap that I hoped was well-crafted. Martin and I in our baggy shorts, Paula in a one-piece… all of us put to shame by this audacity. The suit shone white against his amber skin, hugged the contours of his sex with a voluptuous swell. Michel caught my eye with a silent challenge, each of us remembering—no doubt—that strange evening.

I forced myself to turn away as we started towards the shoreline. Beside me, Paula chuckled.

“Good Lord,” she murmured, in my ear. I smiled and rolled my eyes.

—

Each of us—Paula, Martin and I—were prepared for the chill of the water, having done this many times in the past; Michel was not, shouting and laughing in disbelief as the icy surf enveloped him. Even I had to smile at his antics; he was, no doubt, used to warmer waters—the Mediterranean? the Indian Ocean?—and the easy seduction of the tropics.

We grew quickly accustomed to it, spent nearly an hour dashing back and forth, swimming out as far as we dared, fearing that some undiscovered tide would sweep us away and deposit us days, weeks later upon some distant beach. Presently, though, we grew tired… and hungry.

“We forgot lunch,” I said.

“There’s a store in town, on the main road. We passed it on our way up here. I can go get stuff for sandwiches.” Ever-practical Paula.

“I’ll go with you,” I answered.

“No,” piped up Michel, as he turned to Martin. “Why don’t you go with her, love?”

Martin started, not expecting to be part of this conversation. “I— well, okay… I guess?”

The four of us walked back to our towels. There, Martin tugged his shirt on over his damp trunks; Paula slipped a translucent wrap over her maillot. The store, I was certain, had seen more than its share of half-clad beachgoers and wouldn’t mind two more.

From her purse, ever-practical Paula produced a notepad and a pen. She started a list, consulting with us; not much had to go on it, anyway: bread, meat, cheese, chips, dip, sodas. I fumbled a ten out of my wallet, handed it to her.

“Thanks,” she responded, and the two set off.

“I’m going to go back in,” volunteered Michel.

I stayed back, alone, stretching out on the blanket, soaking in the sun. We were somehow protected, here, in the hummocky dunes tufted with grass; I knew there were others around us, could hear them, but they were invisible. I looked back to the water, could see Michel swimming strongly in the surf, far out, where the shelf of submerged beach dropped away into indigo depths. Part of me wished that he would just keep on swimming, away from us, and let us get back to ourselves, as we once were.

—

I slept, awakened only when Michel returned. He had apparently stopped at the shower—nothing more than a length of pipe and a rusty spout—on his way back to me, to rinse off accumulated sand, and water sparkled like jewels on his nut-brown body, in his coal-black hair. The moisture rendered his suit nearly transparent; I could clearly see the cobra’s head of his manhood outlined under the scrim of cloth, and I looked quickly away.

He toweled himself to dampness and arranged himself beside me, stretching out on his side, arm propping up his head. Again I was drawn to the triangle of white there, again I looked away, face flushing.

“Did you—” My voice came out hoarse and clotted; I cleared my throat and start again. “Did you have a good swim?”

He smiled. “Yes. You should have come back in with me.”

I shook my head. “No. I’ve had enough. After a bit it just gets too cold for me. Too rough. Too… much, maybe.”

He smiled again. “Yes. I imagine it would be.” What he might have meant by that, I didn’t know… but the enigmatic smile gave me pause.

I looked away from him, looked around at the clustered dunes, suddenly all too aware how isolated we were. I swallowed past my nerves. “I think everybody else went to get some food. I think we’re—” I stopped speaking; of course, Michel already knew all of this, had even gone so far as to politely command Martin to go with Paula. He smiled back at me as I blushed with embarrassment and turned away from him, wondering why I felt so tongue-tied.

“Michael…” he murmured.

I turned back at the sound of my name. Michel was sitting, now, legs akimbo, leaning forward, his face only a foot or so away. The breeze stirred his damp, curling goat hair. He sat so close to me that I could feel the combined heat of our bodies between us. I caught hints of his scent—a mix of shampoo, cologne, perspiration—in the air between us and it settled agreeably in my nose.

And then—the slightest movement forward; his face was here, next to mine, his eyes locked to mine, his intent obvious. I reared back, away from him.

“Michel, I’m not Mar—”

He chuckled. “I know, Michael. I know that.” His hand went to the back of my head, drawing me to him, and I did not resist, this time.

I could taste the sea salt on him as we kissed; his tongue forced its way past my lips and into my mouth, a shocking but not unpleasant sensation, although I had never kissed another man before. My hand crept out, found his corded, muscular thigh, came to rest there, feeling the muscles flex and twist as we moved together. Michel’s other hand—the one not forcing my head against his—crept up under the leg of my swimsuit, found its intended target, kneaded me—damn him!—into tumescence under the thin cloth of the swimsuit’s lining.

Michel pulled away slightly, rocked back on his heels, stuck his thumbs into the thin waistband of his swimsuit, raised his hips, preparing to—

Voices, next, and the sound of people approaching: Paula and Martin back from their grocery store run. We pulled away from each other, but not before Michel uttered his frustration in some guttural language I didn’t recognize, then whispered “désolé”—sorry— in my ear before standing up and turning towards the couple. After a few seconds, I stood up, as well, and reached for my shirt to disguise the fading remnants of my arousal.

I could see Paula’s and Martin’s heads, disembodied, bobbing along the tops of the dunes, and then they were here, with us, laughing, talking loudly, each carrying paper bags of groceries, depositing them onto the blanket even as they greeted us.

I could not look Martin in the eye, could see him in my peripheral vision as I busied myself with unpacking the bags, could see the frown on his face as he stared first at me and then at Michel, who—for his part—carried on as usual, as if the attempted seduction of his lover’s brother was something he did every day. Perhaps he did.

I started opening the packages of meat and cheese, wrapped in white butcher paper; Martin worked on a bag of chips, still watching me.

Paula reached into her purse, pulled out a well-used Nikon. “I want pictures of everybody before we eat! Guys?”

We abandoned lunch, followed her dutifully back to the shore. Under her direction, we lined up three abreast, I on one side, Martin on the other, bookending Michel. Martin, unable to get anything out of me, turned all of his attention on Michel, who was all too happy to oblige.

Paula peered through the viewfinder, finger poised over the shutter release. “Ready… wait a minute… ready… okay… smile!”

And we smiled, or two of us did, Martin and Michel. Martin favored Michel, arm wrapped around him, grinning broadly at his lover. Michel gave Paula his full attention, one arm wrapped around Martin’s waist, the other around mine. I—still trying to understand what had happened not ten minutes earlier—turned away just as the shutter clicked, looking down the shore.

What would have happened, had Paula and Martin not have arrived when they did? How far would I have gone? Would I have submitted to his somewhat clumsy seduction? Would we have been discovered, locked together in passion?

What if, if only, perhaps.

—

We worked quickly, efficiently, at preparing lunch. Paula chattered brightly, Martin less so, still not sure what tension was built and building between Michel and me; had he somehow seen something where Paula had not?

In lieu of soda, Paula had bought a couple six-packs of beer, which we happily indulged in; it took the edge off things, made us—well, me—more voluble, if nothing else and I added vapid idiocies to the conversation.

After we ate, Michel and Martin rose, announced that they wanted to go walking down the shoreline a bit, leaving Paula and me sitting there, awkwardly.

“Well…” she started.

I stared at her. She returned my gaze, an unsteady and unsure smile ghosting her face. She gestured at the distant figures of Martin and Michel.

“Do you want to…?” she started, trailing off.

I moved over to her, took her hand again, mind whirling, and I shook my head. I gathered myself, understanding—or thinking that I did—that with this next sentence I would alter the course of my life forever.

I cleared my throat. “Paula… I think I’d like to ask you something.”

—

And then he was gone.

I came home, one evening, to a disconsolate and crying Martin sitting on the sofa.

“What?” I started.

“He’s gone.”

I understood who he referred to. I frowned. “Are you sure?”

Martin snorted. “Of course I’m sure! His stuff is gone, cleaned out. Oh—and he took all the money out of the bowl, too.”

Of course he did, I thought. I couldn’t remember how much had been in there… certainly no more than twenty or thirty dollars, in small bills and bits of change. That’s what he was, I realized, at that point. A thief. Of money, of friendship, of trust. Of love. He’d stolen from all of us in one way or another. Stolen us away from each other.

I sat down beside Martin. “I’m sorry.”

“It wasn’t your fault.” He sniffled and looked around the room, then at me. “I was so stupid.”

“You were in love.”

“You tried to warn me. I should have listened.”

I handed him a tissue. “You were in love.”

I sat next to him on the sofa, commiserating, thinking of my own unwarranted duplicity in all of this. It struck me that this was the closest Martin and I had been to each other in many, many years. Each of us—I think—had his own share of romantic misfortune, but had never found it possible to share it with the other, with the person we were far, far closer to than any other person in our lives. I doubt that any intimacy I shared with Paula would ever supplant that which I had with Martin.

“I thought he was the one,” Martin murmured. “I thought he would stay.”

I thought of Barbara. I thought of the angel and the demon on the balcony of our apartment and at the beach; incubus was not quite the right word for what he was, but it was close enough.

Then you were a fool, I thought but did not say out loud. I don’t blame you, for I was a fool, too.

—

A few days later, we—Martin, Paula and I—met in the Commons, much quieter now than during the school year. A figure stood up from a group of sofas surrounding a muted television and began walking towards us: Robert.

Wordlessly, we scooted our chairs around, making a space for him.

He looked a question at me, glancing sideways at Martin, who sat reading a newspaper. I shook my head, slightly. I looked a similar question at him; he, too, shook his head, slightly.

Later, separately, I asked him about it.

“I went by her place. Deirdre said she hadn’t seen her for weeks. Some of her stuff—clothes, personal stuff—is gone. She left the furniture.”

“Should we call somebody? I mean…”

Robert shook his head. “No. I got… well, we got a note. From her.” He didn’t volunteer to show it to me; I knew I didn’t really need to see it.

“Is she with him?”

He frowned. “I… think so. She didn’t come out and say it directly, but…”

I couldn’t think of anything else to say to him; an awkward silence stretched before he finally spoke again.

“So, uh… you and Paula?”

I smiled. “Looks like it.”

“Congratulations.”

—

Some time after that, I was in the middle of packing; I’d be starting out in a few days with Paula, driving with her to Chicago.

Some impulse led me to take up the cushions in the couch; beside a great deal of stuff like popcorn, raisins and—to my horror—the flattened and desiccated corpse of a mouse, I surfaced with about a dollar and a half of change, which I pocketed. I did the same to the chair next to the couch, hoping I wouldn’t find the partner to the mouse.

I didn’t. Something gold glinted deep in one of the corners and I dug it out.

The Colibri. It had probably fallen out of Michel’s pocket and into the frame of the chair. It was solid and heavy in my hand. I sat in the chair, flicking the lighter on and off.

Later, of course, I showed it to Martin, in his bedroom, where he lounged on the bed, reading a novel.

“Where did you find that?” he asked.

“In the chair. He probably lost it.” I surrendered it to Martin. He stood up and walked over to a wooden box sitting on a shelf. With his back to me, he did something with both hands, opening the box and setting the lighter inside, then closing the box again with a snick! of sound.

The box was something I hadn’t seen before, or at least hadn’t noticed.

“Where did you get that?” I asked.

“What? The box?”

I nodded. He continued.

“Oh… I’ve had it forever. Well, since I was thirteen or so. You don’t remember it?”

I shook my head.

—

Later, when Martin was out running errands, I slipped into his bedroom and over to the box. It was an intricate, beautiful thing, made of some faintly aromatic wood bound with brass wire and decorated with what looked to be semi-precious stones here and there. I tried to open it, couldn’t, spent more than a few minutes inspecting the box, looking for the trick, then giving up. I picked it up; it was heavy. I shook it, heard rattling from within, wondered what—besides the Colibri—rested inside.

A sound at the door was Martin, turning the lock, letting himself in. I tiptoed quietly out of his bedroom and into the toilet, pretended to use it.

The mystery of the box would have to wait.

—

And, then, much later, the email from Robert.

Paula and I were in Chicago by then, still getting used to our first little apartment up on Halstead, a few blocks west of Lincoln Park. I myself was getting used to Chicago itself; I thought I would like it, although with winter coming on, I was about to get an object lesson in four-season climate. Paula delighted in my anxiety, regaling me with stories of snowdrifts up to roofs, the lake completely frozen, gale-force winds howling down the faces of skyscrapers, knocking pedestrians off their feet. It seemed less suitable than Siberia as a place to put a city.

We’d scattered, all of us, soon after Michel left, as we knew we would. The only one who’d stayed in San Francisco was Martin, of course… living in the Castro, of course. He’d met someone, he wrote, and seemed happy. Periodically, he hazarded a visit to our parents house up in Mill Valley. They were faring as well as could be expected, each having staked out “His” and “Her” sections of the house, much like Vietnam or Korea.

Robert went east, to New York and Columbia and what would turn out to be a life-long career in academia; no surprises there, either. Robert, I thought, was the most intelligent of us, the one most devoted to learning.

Of Barbara, we knew nothing.

Until now.

The email was cryptic, typically Robert. It linked me to a video posted on BBC’s news site. “2:45 into it”, was all that Robert said.

I missed it, the first time. The video opened to a talking head in a studio, then cut to a scene of a crowd of people milling about in what looked like a typical London street of Victorian-era flats constructed of grimy red-brown brick, very working-class, by all appearances, a London that most tourists would never see. Central to all of this was someone who looked like a Muslim cleric, being led out of the house by a couple of police personnel, presumably under some kind of detention or arrest. More talking heads showed up. Then the video ended.

I tried again, looking very closely, waiting until the 2:45 mark.

And then I saw it. Her.

Easy to miss, at first. What hair showed under the hijab wasn’t blonde, but brown. But the rest of it, the patrician face and especially the sapphire eyes… unmistakable.

I called him up.

“Incredible,” I began. “How did you find this?”

“I don’t remember, actually. One of the televisions in the Union was tuned to BBC and I happened to be there. I knew it was her, somehow. I just knew. Luckily, they’d also posted it to their website.”

“Was he there?” I didn’t recall seeing anyone who even remotely resembled Michel.

“I don’t think so. That’s not in his nature, you know, to actually commit himself to anything, even something like this. He just… stirred the pot, so to speak.”

I thought of that day on the beach. “Have you shown this to anyone else?”

‘You mean Martin? No. Did you ever tell him?” He and I both knew that Paula wouldn’t be interested in seeing this, wouldn’t care. She and Barbara had never quite made their peace with each other. Barbara thought Paula willfully stupid and shortsighted. For her part, Paula had found Barbara pretentious and judgmental.

“No. Seemed pointless. Even now. He’s met someone, by the way, some artist… Dennis, I think—no, Douglas. Douglas.”

“Good. Good for him.”

We continued the conversation for few more minutes, promising in the end to meet up soon in New York, perhaps for the new year.

After I hung up, I sat there, thinking.

Had Michel known what he was doing when he latched onto our little group? Had he understood what effect his presence would have on the dynamics of our relationships with each other? I had a hard time believing that one person could do the damage he’d done to us, could find our individual weaknesses and prey upon them, prying them apart until we splintered. He’d seized upon Barbara, driven his first wedge between her and Robert. Then, he’d moved on to my brother, seizing upon his fundamental nature by offering himself up as an ersatz lover, only because he needed a place to stay, and—perhaps icing on the cake—driving another wedge between Martin and me. Paradoxically, he’d driven Paula and me closer together, had forced me to figure out, finally, things between us and where I wanted them to go.

But, Stinson…

Were the pieces already in place by the time Michel found us? How tight, really, were the bonds of our friendship? How tight, really, were the bonds we shared with our partners, our lovers? How tight, really, were the bonds of our individual personalities? How well did we know ourselves? I had thought him a catalyst, at one point. Now, I knew him for what he really was. A mirror, held up to us and our vanities.

Barbara, when I talked to her that last time, had let me know that every assumption I—we—had had about her was woefully inadequate; she was not the person we had thought her to be. Seeing her, today, in London, in disguise, having—apparently—abandoned every aspect of her old self had made me understand that.

And, then, of course, me.

I had been within seconds, that day at the beach, of giving myself to Michel and all that that meant. I was ready to surrender myself to his beauty and its promises. In the end, only luck and some reticence on his part had saved me. I would have lost Paula, certainly. I would probably have lost Martin, as well. Michel had, for some perverse reason known only to himself, spared me.

And yet, he’d left me with a new and uncomfortable awareness. Martin and I, it seemed, shared more than just the outward manifestation of our twinned nature. I, as it turned out, was also not the person everyone had thought me to be.

In less than a year, I would be married. After that, who knew? A child, children, a true family? Would it be crueler to run now, to give Paula some awkward excuse, cut my losses—and hers, as well—and acknowledge my truer nature? Or wait twenty years and spring it on her then? Paula and I had talked about fear, that evening at the restaurant; I envied her ability to compartmentalize her life, dividing her future into small, manageable blocks, stepping across them like stones in a walkway.

She had cried, that day at the beach, when I’d proposed to her. So had I, for vastly different reasons, most of them grounded on the fear I had felt that day and felt still.

I had walked on, that first day, after seeing Michel on the plaza. I’d looked back, to be sure, but I’d kept walking. Barbara, for whatever reason, had not, had brought this man and his dangerous and exotic beauty into our group; certainly she couldn’t have known what was going to happen, had seized upon him as only some harmless and cleverly wrought trinket for our joint amusement. Robert, alone, had glimpsed his truer nature, had had the sense to leave before he was sucked under the waves.

I wondered where Michel was now, where he’d wandered to after he’d abandoned us. Was he even now with some other group of people like us, smart and clever and witty, smug in their illusions, thinking themselves safe from harm, marveling over his unconscious beauty, chuckling at his halting speech even as they were charmed by it? As we had been, as we had done.

I wished them well, these people I would never meet. I got up and turned on some lights against the gathering evening, went into the kitchen, started preparing supper, stuck a bottle of white in the refrigerator to chill. Paula would be tired when she got home. She would be hungry.

Public domain image from Wikimedia

Posted 16 November 2024