Breaker Boys

Alan Dwight

alantfraserdwight@gmail.com

I had been a breaker boy since I was seven. That was the year my father died in a coal mine accident, and I, being the oldest child, became responsible for earning money for my family. Fortunately, I didn’t have to earn all that was needed.

I had six brothers and sisters. One was born each year, as my father said, “Like clockwork.” I was the oldest. Two of the children, Mary and Florence, were girls, while Peter, William, Josh, and Joseph, were boys. By the time I was 13, two of my younger brothers, Peter and William, also worked as breaker boys.

I don’t suppose you are familiar with breaker boys, and in fact they no longer exist in America, so I’ll explain.

In the coal mines of Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and other states, young boys, usually aged 8 – 12, were employed sorting the raw coal which was extracted by the miners. The mine used young children because our nimble little fingers were needed. Sometimes, if we remained small and good at the job, we did it until we were 13 or 14, at which time we would be reassigned to jobs down in the shafts.

For 10 hours a day we sat on boards laid over conveyor belts which transported the coal ore out of the mine. Our job was to break up large chunks of coal and get rid of any impurities ─ usually shale ─ tossing it into a side channel. To do that, we temporarily stopped the flow of coal below us by shoving our boots into it.

We worked six days a week and earned about 60 cents a week.

The job was dangerous. Shale can have sharp edges, so cuts, infections and even amputations were common. In addition, boys could get caught in the machinery and dragged to their deaths.

It was tiring, painful, dirty work, and many of us formed permanently bent backs from leaning over all day. There was coal dust everywhere, and I’m sure we all breathed in a lot of it. Coughing was so common nobody paid any attention to it.

Often by the time we finished a day’s work we were too weak to walk home. A man would carry us to a nearby building where we rested until we could stand and walk.

I had been doing the job for seven years. In that time, I got to know many of the other boys, and two, Adam and Luke, had become my special friends.

Luke was my age, 14. Adam was only 10. I knew him because he worked beside me. My name was Zachary, but my friends called me Zach. The only time we had a chance to talk together was on Sundays. The mine didn’t operate on Sundays.

My mother wanted me to go to church on Sunday mornings, but by the time I was 9, I rebelled, telling her it was my only day off and I wanted to spend it my way, not hers.

As for God, we three had agreed that we didn’t believe in Him. How could we? Our lives were miserable, and we reasoned that if God existed, He would have prevented all the accidents and suffering that took place.

Perhaps some of the workers took comfort in God, but the three of us did not. We agreed on two things: there was no God, and we were all scared to death.

Even though I wasn’t going to go to church, I had to bathe on Saturday nights. As the oldest, I carried water from the pump. Mother heated the water and told me to climb in. A perk of being the oldest was that I was the first to bathe and the water was warm and clean. I scrubbed and scrubbed with the stiff bath brush before she did my back. No matter how hard I tried, it seemed as though I never got rid of the coal dust. I guess it was too deep in my pores.

When the first three of us had bathed, Mother poured the water out and sent me for more. I usually complained but that never got me anywhere.

On Sundays, Adam, Luke, and I would meet in a place in the hills which we called ours. Nobody ever bothered us.

Being 14, Luke and I had each discovered the joys provided by our peckers. Living in one-room cottages, we had often observed what our peckers were for, but we never explored them at home because we were too tired and because we all slept with multiple siblings. By Sundays we three were more than ready.

Adam of course did not yet enjoy the feelings we did, although when we dropped our overalls, took hold of our peckers, and began rubbing them, he did the same. He was fascinated by the pecker milk we shot out on the ground. He tried and tried and was disappointed each week when he couldn’t produce any.

In summer we stayed outside until dark, talking, laughing, and playing. On winter Sundays, we went out just long enough to enjoy ourselves a couple of times before returning home to coal fires.

One summer Sunday, as we were heading home at nightfall, Adam asked, as he did every week, how long he would have to wait.

“Until you’re at least 12 and maybe older,” we always told him.

“It’s not fair,” he would complain. We never said the obvious, which was that he didn’t have to be with us if he didn’t want to.

“Look, Adam,” I said, “we had to wait too. And I can tell you that it’s well worth waiting for.”

He grumbled some more but when we left him at his cottage he said, “See ya next Sunday.” Of course he’d see us the other six days of the week, but he knew we couldn’t talk about the fun stuff then.

Monday morning, when the mine bell rang, I untangled myself from my brothers and sisters where we lay on an old mattress on the floor. I climbed into my overalls and trudged to the mine. Sighing, I sat on my bench and waved to my friends. As was often the case, Adam was crying. I think he was the most scared of all of us. The coal started to move, and we began another week of drudgery.

Each night, I dragged myself home, hurting in every joint.

As we arrived at work one Friday, I waved to Adam, who was once again crying. In the middle of the morning, I heard a sudden scream and saw Adam being dragged forward by the conveyor belt. All the boys watched as he disappeared, but we were quickly ordered back to work by the man who was charged with seeing that none of us slacked off.

We knew that Adam was dead. When a boy became caught in the machinery only one outcome was possible. He would be deposited by the conveyor belt when it reached the point where it dropped the coal into bins, but he would be horribly mutilated by then.

We worked silently for the rest of the day, perhaps each one of us thinking that what had happened to Adam could just as easily have happened to us.

Adam’s funeral was on Sunday, the only day the mine wasn’t open. It seemed that all the breaker boys were at the service. Before the service began, Adam’s wood coffin was outside. Usually, coffins were closed for victims of accidents, but at his mother’s insistence his was open. She said she wanted the workers to see what the company had done to her boy.

My brothers Peter and William, as well as Luke and I stared down at Adam’s mangled, destroyed body. I turned to one side and threw up. I wasn’t the only one.

After the service, my brothers went home while Luke and I walked silently to our spot in the hills. We sat, plucking at blades of grass and occasionally sucking on one. It was clear that neither of us felt like milking ourselves that day.

After a long silence, Luke said, “Shit, Zach, are you as sick as I am?”

I nodded. “Yeah, and scared. You know soon we’ll be too big to be breakers and then we’ll be inside the mineshaft, which is even more dangerous.”

“What’ll we do?” he asked.

“Don’t know.”

After a short pause, I said, “Poor, Adam, he so wanted to know what it felt like to shoot pecker milk and now he never will.”

“He was right,” said Luke. “It isn’t fair.”

Like me, he was crying silently.

Again we sat in silence plucking at the grass.

I heard Luke sigh, and then he said, “Well, one thing’s for sure. I’m never going back to that mine.”

“How ya gonna do that?” I asked.

“Guess I’ll run away.”

I thought about that. With Adam and Luke both gone, I’d have no friends.

“Huh,” I said. “Guess I’ll come with ya.”

Without another word, we stood and headed to the nearby hills.

<<<< >>>>

We walked and walked through the woods without really thinking about where we were going. We sweated profusely as we slapped at mosquitoes and occasionally wiped the moisture from our eyes.

I looked around us carefully, wondering if there were bears or wolves nearby.

From time to time we came across a stream and drank deeply.

As the sun began to go down, Luke said, “I’m hungry.”

We usually only ate once a day, after work.

“Me too,” I said, “but I don’t see anything around that we could eat.”

“Nope.”

We trudged on.

When it began to get quite dark, I suggested that we find some place to lie down for the night.

We looked around and found a patch of ground that seemed mossy and without any roots. We lay down, facing each other. After a while Luke said, “Damn. Now I’m horny.”

He stood and lowered his overalls. I did the same. We were both hard, and it didn’t take long for us to shoot.

“This is weird,” he said.

“Yeah, but it’s kinda excitin’ too,” I said, giggling.

We pulled up our overalls and lay back down. Our feet were hurting, so we took off our boots.

I had never known there were animals that went about at night, but I could hear them rustling in the dry leaves. I wondered if any of them were dangerous. Though I was exhausted, it took a long time to get to sleep.

In the night I woke, shivering. I pulled myself up to Luke so our fronts were together. I draped an arm over him and tried again to sleep In the morning, we attempted to put our boots on, but they wouldn’t fit. We didn’t know that, with all the walking, our feet had swelled up. We decided to just leave the boots. That was a big mistake.

We trudged on, still having no goal in mind except to get away from the mine.

We found some mushrooms, but Mother had told me that some of them could be poisonous. We decided not to take the chance.

By nightfall we had walked a long way and had no idea where we were. The Adirondack Mountains rose above us and off to each side. There didn’t seem to be anywhere to go but up.

For a second night we lay together, shivering. By then, our feet were bleeding and, whenever we stepped on sticks or rocks, they hurt, while the blood on them attracted mosquitoes.

Sometime during the night it began to rain, and by morning we were both drenched and cold. We turned towards the mountains and began to climb. On we plodded until we reached a height of land where some flatter land lay in front of us. The view would have been great if it hadn’t been cloudy and raining. A bolt of lightning struck near us. Terrified, we began to race down the other side of the mountain, crying with the pain in our feet.

Late in the afternoon we heard some rustling and grunting ahead of us. Moving cautiously and peering through the leaves, we saw a mother bear and two cubs in a clearing where they were eating blackberries.

We both knew that a mother bear with cubs could be dangerous, so we backed up and decided to wait until they left.

When they were gone, we searched for berries and found just enough to make us even hungrier. We guessed the bears had eaten most of them.

As it began to get dark we tried to pull some downed branches together to make a shelter from the rain, but finally gave up and lay in the rain.

Sometime during the night, the rain stopped and the stars came out. We took off our wet overalls and lay naked together, holding each other for warmth.

In the morning, we had to force ourselves to stand and go on, crying in pain and cold from time to time. Other than a few berries, we had had nothing to eat since the previous Saturday night. We were both feeling weak, and we knew we had to find food if we were going to survive. I wondered if this was any better than working in the mine, but I didn’t say anything to Luke.

As we descended barefoot into a valley, we each fell several times, our legs simply giving out.

Suddenly, Luke stopped and sniffed the air. The wind was blowing gently towards us, and he asked, “D’ya smell that?”

I didn’t at first, but then I caught the scent of old, rotting apples. Perhaps, I thought, where there were rotting apples there were also ripe ones.

We forged on in the direction of what we could smell, and in about half an hour we came to an old orchard. It seemed like there were hundreds of trees heavy with fruit. Without hesitating, we plucked apples from the lowest branches and devoured them.

We ate and ate, desperately trying to allay our hunger. When we could eat no more, we sank to the ground and slept, although it was only midday.

I awoke to terrible stomach cramps. Rolling on the ground and holding my belly, I groaned and cried out. That awoke Luke, who was soon in as much discomfort as I was.

We screamed and cried, rolling about trying to escape the pain.

I heard a voice say, “What the hell ya doin’ here?”

Looking up I saw a man standing near us with a hoe in his hand. Like us he wore overalls. Unlike us, he had boots on. He had a scruffy beard and hair hanging to his shoulders.

“Who are ya?” he asked.

“Zachary,” I gasped.

“What are ya’ doin’ here? D’ja run away?”

“Yeah,” I said, as tears ran down my face.

“Who’s that?” he asked, pointing.

“Luke,” I said.

“Where d’ja come from?”

“T’other side o’ the mountain,” I stammered.

“Hmpf. Yer on my land.”

“Sorry. We was starvin’.”

“Help us,” sobbed Luke.”

“Why should I? Ya was stealin’ my apples.”

I felt something rising in my throat. “Oh God,” I said and vomited, emptying my stomach of all I had eaten.

“Feel better?” the man asked.

I realized that in fact I did. “Yeah,” I answered.

Just then, Luke threw up and then lay back, moaning.

“Well,” the man said, “ya can’t stay here in the orchard. Come with me.”

It took me several tries to stand and lean on a tree.

“I don’t think I can walk,” I said.

“Suit yerself,” he said, and began to walk away.

“Wait,” said Luke, “Can’t you help us?”

“What can ya do fer me ef I do?”

I looked at Luke and then said, “We could work fer ya.”

I could see the man thinking about that before he said, “Come along then.”

I took two steps and fell to the ground.

With me leaning on his left arm and Luke on his right, we made our slow way through the orchard and fields to a farmhouse. It had been painted white at some point, but much of the paint was gone and here and there a board had fallen off. Behind it was a barn which had once been red.

The man told us to sit on the back porch of the house while he went inside.

“Martha,” he called, “we got vis’tors.”

When he came out a few minutes later he was carrying a tray with two bowls on it. He handed one to each of us, along with a spoon, and told us that if we kept the soup down, he’d give us something more later.

As we ate, a woman came out of the house and looked at us.

“Land sakes, Walter,” she asked, “who are they?”

“Dunno,” he replied. “Found ‘em in the orchard eatin’ apples that wasn’t ripe yet. By the time I found ‘em, they was throwin’ up. They was real weak , couldn’t hardly stand, so I brang ‘em here.”

When she asked where we were from, Luke said, “T’other side of the mountain.”

“When’s the last time ya et?” she asked.

“Saturday night,” I answered.

“No wonder ya was eatin’ apples,” she said.

When we finished the soup, Walter helped us up and into the house.

“You boys tired?” Martha asked.

“Yes, ma’am,” I said.

“Well, we don’t have an extra bed, but there’s a corn husk mattress in t’other room,” she said.

“That’s fine,” Luke said. “We hasn’t ever slept on a bed. We slept on the floor with our brothers and sisters.”

Carrying a candle holder with a lit candle, Walter led us to a room while Martha got us a quilt.

“Did ya make this?” I asked. “It’s beautiful.”

She blushed but said nothing.

Luke and I eased ourselves onto the mattress.

“Take off yer overalls,” said Walter, “You’ll be more comfortable.”

We pulled the quilt over ourselves and then wriggled out of our overalls.

“Y’don’t hafta hide anythin’,” Martha said. “We’ve had sons and I’ve seen everythin’ ya got.”

It was our turn to blush.

“If ya need the outhouse,” Walter said, “it’s rat out back.” He blew out the candle and they left the room.

I was asleep before they were gone.

In the middle of the night, I woke up knowing that I needed the outhouse badly.

I climbed up off the mattress. I was terribly stiff, and walking was still painful. I found a back door to the house. The moon was almost full, and it lit my way to the outhouse, where I sat and relieved myself.

Back in the house, I crawled onto the mattress and covered myself with the quilt. I don’t think Luke was awake, but he curled into me and threw his arm over my side. We slept that way until morning.

<<<< >>>>

We were still asleep when Walter called us. We put on our overalls and hobbled drowsily to the kitchen, where Martha was cooking eggs and toast on the coal stove.

As we ate, Walter asked, “Have ya ever lived on a farm b’fore?”

“No, sir,” I said. “We worked in a coal mine.”

“At yer age?” Martha asked.

“Yes, ma’am,” I answered. “I b’gan workin’ when I were seven.”

“That should be criminal,” she said.

“Ten hours a day, six days a week,” I said. She just shook her head.

After breakfast, Martha wrapped our feet in rags and Walter took us first to the barn, where he introduced us to the animals. There were chickens which they raised for meat and eggs, pigs which they raised for meat, a couple of cows they kept for milk, and two plow horses. He showed us how to collect the eggs without upsetting the hens and then how to milk the cows.

From there he took us out to his garden, showing us where corn and other vegetables were growing. He gave us each a hoe and taught us how to dig up the weeds without damaging the crops.

We worked in the field until Martha rang an iron triangle on the porch, calling us in to dinner.

She put meat and vegetables on the table and told us to dig in.

Neither Luke nor I had ever eaten more than one meal a day, but our bodies were still feeling the effects of our foodless days, so we had no difficulty putting away a sizable amount of food.

After dinner we returned to the field and worked the entire afternoon. By the time the triangle rang again, both our backs and arms were bright red and hurting.

Martha noticed our backs as soon as we went into the house, and she got some sort of salve which she rubbed on our backs while we applied it to our arms.

When it began to grow dark, we went into our room, stripped off our overalls, and lay face down on the mattress. We pulled the quilt up over us, but it hurt our backs, so we put it to one side.

In the next few days our backs and arms blistered and then peeled. We began to have a nice tan, and our feet were healing. Being breaker boys and working inside, neither of us had ever had a tan before.

The one thing that remained from our former life was the Saturday night bath. When Martha began to lug water for it, we took the pails and did it ourselves while she heated the water. Realizing that we might want privacy, she left us in the kitchen to bathe while she and Walter went into their living room.

As Luke and I took turns in the water, he said, “I’m feelin’ real horny. What d’we do ‘bout that?”

“Wait ‘til we’re in bed and I’ll tell ya,” I said.

Luke was curious, but I wouldn’t say any more.

As we lay on the mattress that night, Luke said, “Well? Tell me.”

I knew that the problem was what would happen to our pecker milk. We certainly didn’t want to get it on the quilt or the mattress, so I could only think of one solution.

“Lie on yer back,” I said.

When he did, I said, “Now git yerself hard.”

His hand moved to his pecker and he began to stroke it.

When he was hard he asked, “Now what?”

I leaned over him and took his pecker in my mouth, caressing it with my tongue and lips.

“Oh!” he groaned. “Oooooh!”

I took my mouth off him for a minute and asked, “D’ya like that?”

“Oh, yeah! Don’t stop!”

I was no expert, but I went back to work and soon he was shooting his milk into my mouth.

When he finished and I lay back, he said, “That were amazin’. I never thought of doin’ that.”

“Now do me,” I said. And he did.

We slept peacefully in each other’s arms through the night.

First came friendship, but through the summer it became something else ─ love.

Don’t get me wrong. Sex was part of it, but it was my feelings for him and his for me that turned to love. When he was off working somewhere else on the farm, I missed him. I wanted him with me. When he injured his foot with a hoe one day, I was truly concerned, and I watched carefully for signs of infection. Matha cleaned the wound out well, and there never was any.

One day, seemingly out of the blue, Walter said, “You boys seem to git along real well t’gether.”

I wondered if he suspected what we were doing at night. If he did, that was the closest he ever came to saying anything.

Even when winter came, and it was a hard, cold one, we always slept naked. Martha made us wool shirts to wear with our overalls. Walter got us some long johns in town. I suppose we would have been warmer wearing them in bed, but we didn’t want to give up our nightly activities.

After spring plowing and planting, Luke suggested that we paint the house and barn. Walter fussed some about the cost, but Martha was on our side, and Walter gave in. Unlike our work as breaker boys, we enjoyed the painting and felt a sense of accomplishment as we watched the house and barn emerge in their fresh colors.

In fact, we enjoyed all our work on the farm. Being outside in the fields was so much better than being in the mine. We didn’t mind hard work and we enjoyed contributing to Walter’s and Martha’s food supply.

One night, Luke said, “Ya know, I been watchin’ the pigs mate. It’s kinda funny but it give me a idear.”

From under the covers he produced the jar of salve we’d used on our backs in the summer.

“Git up on all fours,” he said.

I did, and I immediately felt him poking around my butthole.

“What’re ya doin’?” I asked.

I could feel him putting some of the salve on my butthole before he stuck a finger in. I told him that felt real good, and he put in two fingers. Then he said he was putting some ointment on his pecker.

“Brace yerself,” he said. I felt the end of his pecker on my hole. He pushed, but my hole resisted.

“This might hurt,” he said, and pushed harder.

He was right, it did hurt, and I cried out, “Ow!”

“Sssh,” he said quietly. “D’ya want me t’ stop?”

I considered some and then said, “No. Jes’ go slow.”

Again he worked my hole with his fingers, then I felt the pressure on my hole, and again he pushed, this time harder. The pain was awful, but then he seemed to get past my hole and slid in more easily.

“You okay?” he asked.

“Yah, jes’ let me rest a minute.” When the pain was gone, I said, “Okay, keep goin’.”

Farther in he met more resistance, and I wasn’t sure I could stand any more pain, but then the resistance gave way and he slid all the way in.

“You okay?” he asked again.

“Yeh.”

How does it feel?”

“Like I’m really full back there, but really good.”

He began to move his pecker slowly out and in, out and in. At one point it touched something that felt so good I moaned.

“Oh, my! Keep doin’ that,” I said, enjoying the sensation of him inside me.

He did.

It wasn’t long before he shoved in hard, and then I could feel his pecker throbbing in my butt, and I knew he was shooting his milk into me. I began to shoot my milk, trying to collect it onto my hand. As I did, I felt my butt muscles tighten, and he oohed and aahed as we shot together.

<<<< >>>>

In the fall, when we went into town, we began to hear rumors of runaway boys from the mine. We may have been the first, but we certainly weren’t the last. We also heard it said that when Luke and me ran away, we tried to live in the woods and that we had died there. Another tale was that we were kidnapping breaker boys and selling them to work as slaves on farms. We had to laugh at that one.

Walter and Martha were both old. When Martha died, we helped Walter bury her in her flower garden. It was then that he signed the farm over to us, before, broken hearted, he soon followed her.

One winter day, as we sat before a fire in the living room which was now ours, we remembered the tale of us kidnapping some boys.

“Why not?” asked Luke. “They’d be a lot better off with us than they are in the mine.”

As we talked, we became convinced that we could succeed in bringing boys to the farm. We knew that kidnapping was illegal, and we certainly didn’t intend to sell them as slaves, but we thought that what was happening to young breaker boys should also be illegal, as Martha had said.

So, in the spring, after our early plowing and planting were done, we loaded up packs with food and blankets and set off back across the mountains.

We had to go up and over the mountains, but in Pennsylvania they’re only about 3100 feet high. I felt the walk was invigorating, but I could see Luke laboring some, stopping often to catch his breath. As we neared the summit of the ridge, he was coughing as well.

We ended up several miles from the mine, so we trekked through the edge of the woods until we could see and smell the mine. From there we made our way to the clearing where we had played on Sundays. Sure enough, on Sunday morning, three boys appeared as we stood back a ways in the woods, unobserved. It was clear from their size, their clothing, and the coal dust on them that they were breaker boys.

They immediately dropped their overalls and began stroking themselves. We emerged from the woods and walked toward them. One of them looked up, saw us, and said, “Oh, shit!”

As the three began to pull up their overalls, I said, “Don’t worry, boys. Yer safe with us.”

One boy, who we learned was Jacob, and the oldest, stood in front of the other two, shielding them. He asked, “Are ya the guys from the woods what kidnaps boys?”

“Yes and no, but mostly no,” said Luke. “We’re from t'other side of the mountains, and we don’t kidnap boys. But, if ya choose t’ come with us, we kin promise you a better life than yer livin’ now.”

“How do we know we kin trust ya?”

“Ya don’t,” I said, “but also ya don’t have much to lose.”

“Only ar lives,” he said.

“Okay,” I said, “let’s talk ‘bout yer lives.”

Luke and I sat down and invited the boys to do the same. They did, but far enough away from us that they could run if they felt threatened.

“We was once breaker boys, and we know what yer lives are like.” Luke said. “They’re nothin’ but long hard days, aching backs, not enough food, danger, and a pittance fer pay. Like you we used t’ come here on Sundays with another boy. He was younger, and one day while he was workin’, he was caught in the machinery and dragged t’ his death.”

The boys looked at each other.

“Luke and me decided t’ run away, and we did,” I said. “We didn’t have any food and the nights was cold. We almost died.”

“But,” said Luke, “Zach and I made it over the mountains and down t’other side to a farm. I’m not sher we would’ve lived another day, but the man there and his wife took us in, fed us, an’ took care of us.”

“Since then, we’ve worked on the farm,” I went on, “and I can assure ya it’s much better than working as a breaker. So, we decided if we could help a few boys t’ enjoy a better life with us we’d try t’ find some.”

“You’d take us t’ the farm, but then we’d work there?” Jacob asked.

I nodded.

“How do we know ya won’t jes make us work fer ya, like slaves?”

“Well, we didn’t know that either when the farmer took us in, but we figured we could always run away from the farm if we needed. We didn’t. The farmer and his wife have died, but we’re still there, and we hope you’ll join us,” I said.

Jacob and the other boys huddled together and talked. At length, Jacob turned to us and said, “We’ll try it, but we wanna walk apart from ya so we can get away if we need t’.”

The first thing we did was feed the boys, the food disappearing quickly. Then we picked up our packs and, with the boys following behind, walked into the woods and headed up into the mountains.

Again, Luke seemed to labor some as we climbed, and again he stopped often to catch his breath. He coughed and spit some too, and his spit was black.

When it began to grow dark, we found a place where we could stretch out for the night. We and the boys ate some of our food while we told the boys about stealing the apples and getting sick. We gave them each a blanket in which they could wrap themselves.

Still not trusting us, the boys decided that they would take turns keeping watch. Luke and I lay separate from them, while Jacob sat leaning up against a tree. The other two were soon asleep.

They must have traded watchers during the night, because when we woke in the morning, one of the boys, Noah, was awake.

As we had some breakfast, I asked the boys, “Where are yer boots?”

“They don’t fit no more,” replied Jacob.

“Well, bring ‘em with ya. You’ll need ‘em later.”

Having never hiked before, the boys were rather stiff and their feet were sore when we set out, but they kept up gamely. We walked up and down hills, gradually climbing higher. By late afternoon, we were almost at the ridge and decided to camp again, believing that the descent the following day would be easier.

It may not have been easier but it sure was faster, and by afternoon on the third day we reached flat land not far from our farm.

Walking through the familiar fields, I pointed out the barn and house we had painted.

By then the boys had relaxed and begun to trust us. I took them into the house while Luke sat on the porch, panting. I showed the boys where they would sleep. They had the bed because it was big enough for three small boys and because Luke and I still never wanted to sleep in a bed.

As it began to grow dark, we fixed a filling supper for them, which they demolished rapidly, and then we suggested they go to bed.

There was still some moonlight shining through their bedroom window, and as I passed their room a few minutes later I saw three pairs of overalls thrown on the floor. I smiled and shut the door quietly.

Luke and I sat in the kitchen for a time. I told him I was worried about his breathing, but he didn’t seem concerned. I reminded him that he’d been coughing for years and sometimes spitting up black mucus.

“It’s always been hard fer me t’ breathe,” he said. “I think it’s the coal dust in m’ lungs. “

In the morning Luke called the boys while I prepared breakfast. I noticed that they were going barefoot, as were we, and I saw they had worn some blisters on their trek to the farm. When we finished breakfast, I put some salve on their blisters and wrapped their feet in old cloths. I told them to be sure to keep their feet clean if the blisters broke.

Luke and I took them outside to the barn, where we introduced them to the animals. I could see that Daniel, the youngest of the three, was afraid of the larger animals, so I put him in charge of feeding the chickens and gathering the eggs.

Noah fed the pigs while Jacob fed the plow horses and the cows. Then I showed them all how to milk a cow.

Jacob muttered something which I didn’t understand, so I asked him. He blushed and said, “It’s kinda like jerking m’self and shootin’ pecker milk.”

“Yes,” I said, “but I suspect you enjoy jerking yerself more than the cows enjoy bein’ milked.”

We all laughed.

For the rest of the morning, we put the boys to work alongside us in the fields, hoeing and weeding.

The remainder of the summer passed as the boys adjusted to working on a farm. They were willing workers and never complained. At first their backs burned like ours had the first summer we’d worked there, and I gave them some ointment which they spread on each other’s backs.

The ointment jar disappeared, and I wondered if the boys were using it as we had.

They ate well and slept well. If they indulged like us in nighttime activities, we didn’t hear them. We knew they were very close, but we never intruded.

As Luke and I grew older, we had wills drawn up which left the farm to the three boys.

We also had some improvements made. When electric lines were extended to us, we installed running water and a hot water heater so that we could take hot showers. The boys were enthralled, and tended to linger in the shower until the hot water ran out, but we worked out a schedule and a time limit so we could all get clean.

We kept the wood stove. Fuel was easily available in the woods, and we had learned to cook on it.

“Zach,” Luke said to me one day, “the smartest thing we ever done was t’ run away from the mine.”

“And,” I agreed, “the second smartest thing was t’ bring the boys here.”

Luke’s breathing and coughing continued to grow worse, and one day I found him lying dead in a field. I assumed that the coal dust had gotten him at last. He was only 41.

The boys and I buried him in the garden with Walter and Martha.

I continued working on the farm with the boys, now young men, until I became too old to work. I had arthritis in most all my joints, and the pain when I moved, especially in winter, grew excruciating.

The boys took care of me as I grew weaker.

When I knew my end was close, I asked them to bury me beside Luke, my true love.

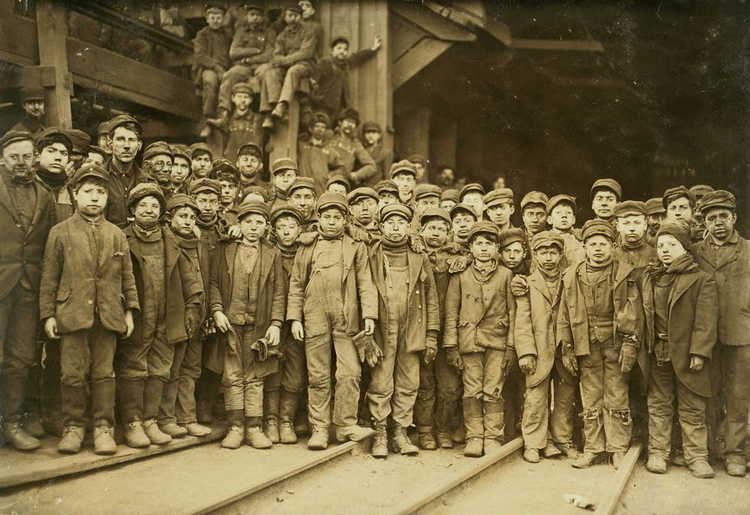

The photos accompanying this story were taken by Lewis Hine in a coal mine in Pennsylvania in the early 1900s. His pictures of children working in mines and mills did much to end the employment of children in the American workforce.

As always, many thanks to my editors, without whom this would be a much different story.

Please consider donating to AD so that the website can continue.

Photos by Lewis Hine

National Child Labor Committee

collection

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division